Since the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, the activities of any government, company, academic institution or any other organisation that take place in, or have an effect on, the environment above and beyond Earth’s atmosphere (and sometimes within it), have been regulated by space laws and policies.

Today, anyone working in this field will at some point encounter legal issues relating to the entry and use of space, protection of the space environment, insuring of missions and equipment, and several other areas that needs to be dealt with properly.

In this article we give a brief overview of some of the major pieces of space legislation in force and review areas of the field that the small satellite supply chain should be aware of.

We begin with efforts by the United Nations (UN) to define and codify legislation relating to space.

The Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPOUS)

Formed by the UN General Assembly in 1959, the Committee governs the use and exploration of space for the benefit of humanity in terms of peace, security and development.

Two subsidiary bodies were established in 1961; the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee and the Legal Subcommittee, and today COPOUS performs a vital role in monitoring and responding to legal space issues at a global level.

The Committee was instrumental in the creation of the five treaties and five principles of outer space which arguably form the bedrock of most space laws that apply to companies, governments and researchers today.

This collection of legislation is usually referred to as the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, or simply the Outer Space Treaty for short.

The UN has been instrumental in the development of effective legal frameworks that govern how space can be accessed, understood and used by all nations and companies with the ability to do so.

In international law the majority of space-related legislation is based upon these treaties and principles at some level. Here they are in more detail:

The 5 UN treaties on outer space

The Outer Space Treaty – this is the basis of most space law and covers issues such as limiting the use of the Moon and other bodies for peaceful purposes, and preventing the placement of nuclear weapons in space. It was first agreed between the USA, UK and Soviet Union in 1967 and to date over 100 other countries have become party to it.

The Rescue Agreement – this legislation compels countries to take all possible action to help and to rescue astronauts in distress, and return them to their home nation. It also stipulates that states should help recover and return objects that land on Earth outside of the territory from where they launched.

The Liability Convention – also known as the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, this agreement ensures that the country which caused a launch to occur is liable for any damage that may be caused by that launch. The only claim that has so far been made under this convention was in 1978 when the nuclear-powered Soviet satellite Kosmos 954 crashed in northern Canada, leading to a costly cleanup called Operation Morning Light. Following arbitration, under the terms of the treaty, the Soviet Union eventually paid Canada C$3 million.

The Registration Convention – with the full title Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, this 1976 law has been ratified by 69 states and requires each of those to give the UN details about the orbit of every space object launched from their territory. A registry of these objects is maintained with the aim of understanding how best to use and manage orbits to ensure sustainability and safety in space.

The Moon Agreement – this piece of legislation, which came fully into force in 1984, expands on aspects of the Outer Space Treaty relating to the Moon and other celestial bodies. It stipulates that these locations should only be used for peaceful purposes, that disruption to their environments should be minimised, and that the UN should be given the location and purposes of all stations and facilities established on these bodies.

The 5 UN declarations and legal principles on outer space

Establishing effective international law requires agreement on a common set of definitions and principles to ensure that all stakeholders understand and appreciate the detail.

In order to develop and strengthen the existing body of law, the UN has developed five sets of technical and legal principles with the following titles:

- The Declaration of Legal Principles – specifying the guiding principles of the Outer Space Treaty.

- The Broadcasting Principles – rules governing broadcast responsibilities and activity.

- The Remote Sensing Principles – legal definitions pertaining to the use of space-based sensing equipment to identify and characterise natural resources on Earth.

- The Nuclear Power Sources Principles – detailing how to protect people from the effects of nuclear radiation from spacecraft using such power systems in the event of an accident.

- The Benefits Declaration – a 1996 declaration that space exploration should be undertaken for the benefits of all states.

If you are interested in understanding more about the technical details held in these sets of principles, the best place to start is the website of the COPUOS which has been included in the references list below.

Together with the five treaties, these principles have formed the basis of a rich body of law that has governed space activity for decades with reasonable success. However, recent innovations in the small satellite sector have led to some instances where new legislation is needed and the existing rules have been updated for the latest industry requirements.

Small satellite laws and legal issues

In recent years small satellites have become a major driver of space industry growth and innovation. New launch options, miniaturised components and low-volume payloads have lowered the costs and barriers to accessing space for stakeholders all around the world.

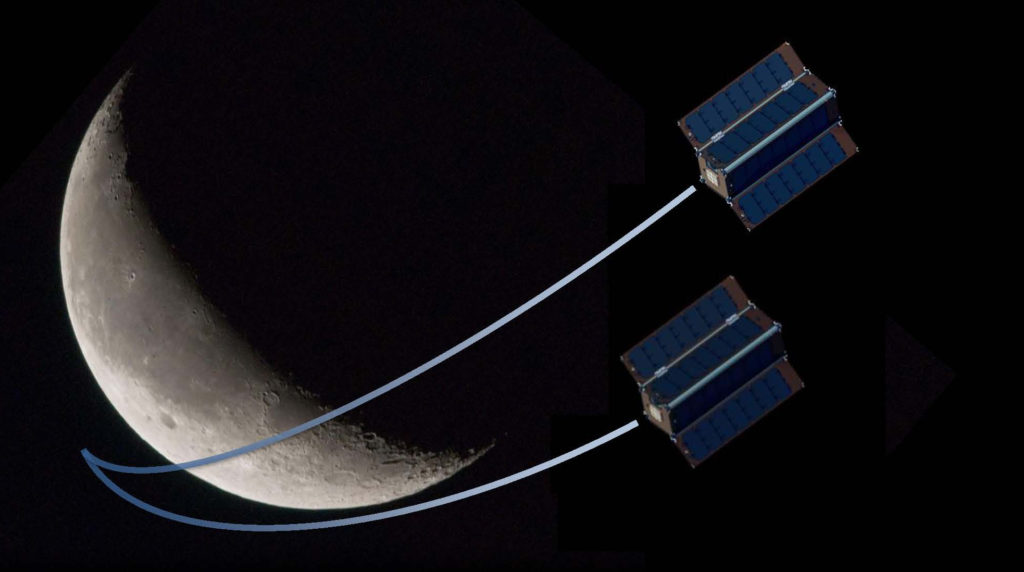

While many aspects of the launch, operation and decommissioning of small satellites (CubeSats, nanosats etc.) are covered by the Outer Space Treaty, there are some specific areas where existing regulations need particular attention or are being tested such as:

Launch safety – prospective satellite owner-operators are usually required to demonstrate that the launch solution they have elected to use doesn’t pose a risk to human health. Where smallsats are concerned the launch provider is often contracted and liability needs to be clearly defined and understood by all parties.

Failure rate – small satellites can have a higher failure rate than larger systems. Equipment failures, and the resulting knock-on effects that can be caused, need to be factored in to compliance and insurance requirements.

De-commissioning – we’re all aware of the growing threat of space debris and the need for satellite missions to consider effective mitigation strategies. In particular, regulators are increasingly pressuring operators to demonstrate how they plan to deal with equipment reaching the end of its life.

Control – although we are seeing a growing number of in-space propulsion systems come to the market, many small satellites can still only be controlled to a very small extent, if at all, once in orbit. This provides challenges in both a practical sense (e.g. how can a smallsat avoid a collision if it cannot maneuver?) and a legal sense (e.g. who is responsible, and what does responsibility actually mean, for a satellite that cannot be controlled?) Even when ongoing control is possible, legal issues can still be complex if the operators are based in more than one territory and possibly subject to different national laws. This will be particularly important for constellation operators for instance.

Humble heritage – traditionally, some of the larger stakeholders in the industry have viewed smallsats as being for hobbyists, not the domain of businesses with the resources to adhere to strict compliance rules. Although this perception is changing as the market develops, it is important for smallsat operators to demonstrate the capability to gain authorisation under space law and engage effectively with relevant international rules, such as frequency coordination regulated by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

Location of ground station or ground segment operations – the territory in which the ground segment servicing a particular satellite is based will usually define which national laws will apply to the satellite’s activity. In order to reduce the requirements on satellite operators, companies such as satsearch member Leaf Space are offering ground segment-as-a-service solutions that have the potential to lower costs and, crucially, simplify compliance.

Tracking and registration – it is important that relevant national and international bodies are made aware of the launch of any new satellites from their territory or that can affect the citizens they protect. In some cases a lack of adherence to this law has led to significant issues, such as a $900,000 bill levied at Swarm Technologies, Inc. by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for the unauthorised launch and deployment of four satellites in 2018.

Radio band licensing – in order to communicate effectively smallsats often use radio transmission systems that need to be registered and licensed to ensure they don’t affect other systems, on and off Earth. Complying with the relevant legislation in this area can be time-consuming though it is very important to minimise the potential for disruption. One emerging alternative is the use of laser communication pioneered by companies such as satsearch member AAC Clyde Space, who have developed a modular lasercomms system called CubeCat, and it will be interesting to see how regulation of this field develops in the future.

Other major issues

There are several other areas where space legislation is becoming increasingly important to activity and growth in the modern industry and many of these are expected to be tested in the short- to medium-term, for example:

- Ownership of asteroids, planets, the Moon and other celestial bodies,

- Mining and extracting resources in space – including safety, rights, transport and debris risks,

- Travel and transport between space stations and celestial bodies,

- The emerging possibility of carrying out commerce in space,

- Militarisation – see recent anti-satellite tests and plans for a US Space Force for example,

- The control and legislation of satellite-based Internet of Things (IoT) devices in and from orbit,

- Legislation governing international cooperation on planetary defence, and

- Basing blockchain assets in space to enable de-centralised currencies or other value systems free from national and international oversight.

We’ll dig into some of the issues more deeply in the future, but if you have any questions or comments about specific areas of space legislation that relate to your work, we’d love to hear from you. Please feel free to email [email protected] with any feedback.

Sources and further reading

If you are interested in finding out more about what space law is and how it can affect your company’s operations, the following links are a good place to start:

- Website of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS)

- The five treaties and five principles of outer space

- International Law Perspectives on Small Satellites Activities

- To Infinity and Beyond: Space Law 101 by the American Bar Association

- Who Owns the Moon? Space Law and Outer Space Treaties

- Space treaties are a challenge to launching small satellites in orbit